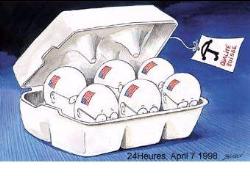

Brain drain or mutual gain???

By basuanand

@basuanand (1)

India

November 3, 2006 6:41am CST

BRAIN DRAIN is not a phrase that one hears frequently these days, not in India and not in the West. It is not that the number of students or young professionals who leave India has come down. On the contrary, in 2005 the number of Indian students joining universities in the United States reached an all time high at over 80,000. India for the first time became the largest source of foreign students to the U.S., overtaking China in the process. The same may be true generally of the United Kingdom, Australia, etc. And yet neither side worries excessively about either the brain drain or being overwhelmed by this flow. Why?

The answer lies in the changing dynamics domestically and globally. And it is a dynamics that is as yet unfolding.

The worries about the brain drain were a phenomenon of the 1970s and the 1980s and quite legitimate from a national point of view. The best and the brightest from the IITs, to name the most premier category in the outflow, migrated in droves to the U.S. It is understandable that this was deemed a loss at a societal and national level.

Here were these elite institutions, built and operated as a national project with substantial resources and commitment, attracting the competent after a fierce competition, and producing world class engineers and technologists as products of quality education, at virtually a nominal cost.

And the result? It was rewarding for the individual no doubt, but questionable for society. "When one joins the IIT, after the first year it is only the body that is in India; the heart and the soul is already sold to the U.S.," it was said with some justification, though this was a sweeping generalisation and there were many honourable exceptions.

According to one figure, there are more than 30,000 ex-IITians in the U.S. Medical professionals migrating to the West followed a more complicated route and yet, according to one estimate, there are more than 70,000 doctors of Indian origin in the U.S. alone. Similarly, there are large numbers elsewhere in the West, and not only in the West. Many thousands found greener pastures in the not-so-green desert in the Gulf. Today, the Indian diaspora all over the world is estimated at more than 20 million but there does not seem to be a figure for professionals as such. However, the outflow of Indians with talent, training, and technical skills has been a notable feature in the country's recent outward migration pattern.

If we have stopped talking of this phenomenon as a "drain," and are beginning to see it as a more complex reality of Indian society, it is for a number of reasons.

To start with the mundane and the material, even in the heyday of the talk about the brain drain (not all that long ago), there was a counter argument that the country benefited from the remittances of the then precious foreign exchange such NRIs sent. It is doubtful whether India gained significantly from remittances from NRIs in the West. In fact, the substantial remittances were from our workers in the Gulf rather than from the professionals saving or investing their money in the developed world.

There was the more tenable argument that there were better opportunities for such an elite in the West than in India and that in terms of their professional development they were better off being productively engaged in the West than facing frustrations in India. It was also believed that with our abundant endowments in "human resources" and the existing infrastructure in education, India would always have enough and more from the pool that produced such professionals and could thus afford the outflow.

In an empirical sense this has turned out to be the case, though an economist may have an alternative perspective on how the state has subsidised our educated elite, a section of which has contributed to another society and not ours. Besides all this is a basic fact which is not stated but has to be accepted: we are simply not the type of polity or society that can either control or regulate the outflow of talent in search of opportunities outside if they are deemed better. We are just incapable of any such regimentation.

Irrespective of the merits or the demerits of the above arguments, the point being made here is that the picture has been changing since the 1990s in a number of ways and the loss-gain calculus is more complex.

The psychological and the sociological impact of the Indian success story abroad on India is perhaps yet to be analysed. In the last two decades, as many Indian professionals and entrepreneurs did really well, they contributed to changing perceptions about India and Indians in an international context. The value of this for India cannot be quantified but is nevertheless very real. Indian professionals in that sense - teachers, doctors, engineers or accountants - were instruments in changing the image of India. This process took a quantum jump with our success in the Information Technology sector, which does require a special mention as today it has become synonymous globally with India's changing profile. The substantial presence, profile, and accomplishments of Indians in the Silicon Valley have also gradually led to replication of some of the business models in India, leading to our own much heralded success in this area.

Exaggerated?

Another word about the IT success may be in order. Is it exaggerated and blown out of all proportion? It is fair to say that the IT sector is a microcosm, employs a minuscule percentage of the workforce in the Indian context and should not lead us to the illusion of India shining everywhere. However, there are other qualitative aspects. Irrespective of the numbers, the IT success has given us a confidence to compete and excel with the best in the world, has imbued many young people with a "can do" attitude, and, equally importantly, has changed the image of India. Equally importantly, in real terms it has changed the notion of the locale and the workstation and has given us some early advantages in being plugged into a global system where national boundaries are getting blurred for an increasing number of knowledge workers.

Seen in another way, the flows in work, revenue, and travel are going to get more complex and multi-vectoral than before.

This picture has been changing more rapidly since 2000. With our sustained economic growth and the increasing opportunities in India for the skilled and the competent, distant shores may not shine as brightly as before. The rising remuneration levels in India, the exciting and energising work environment, the spread of outsourcing and offshoring to India by major global corporations, the emergence of world class Indian companies that compare favourably with the best in the world to attract and retain talent -these are only some of the factors that will change the paradigm of brain flow in one direction.

In fact we are already witnessing bright engineers from the U.S. wanting to intern or work in India as it will look good on their bio-profile; some long-term residents in the West returning for reasons of more attractive opportunities or better quality of life; leading Indian companies hiring more foreigners for diversity, etc. Being close to the Silicon Valley, this writer sees all this as a part of his day-to-day professional work.

It is not the contention here that the brain drain has been reversed or that India can be complacent with regard to its technologically trained manpower or that we can even meet our own requirements. (A recent study by the National Association of Software and Service Companies[NASSCOM] for instance demonstrates how we will have shortages even in fields such as IT where we have strengths.) There are many issues to be addressed. But it is important to realise that it is an increasingly shrinking world, especially for the "brains"; what we need is a more sophisticated understanding of the national-international dynamics at work, at the workplace.

(B.S. Prakash is India's Consul General in San Francisco and can be reached at cg@cgisf.org)

No responses